Launching ClimateLearn

ClimateLearn is a Python library for accessing state-of-the-art climate data and machine learning models in a standardized, straightforward way.

Background

In recent years, extreme weather events have made more apparent the threat of climate change. Atlantic hurricanes slamming the eastern United States have been increasing in intensity and severity. Torrential downpours submerged much of Pakistan underwater, killing thousands of people. Unprecedented heat waves sparked wildfires that tore through swaths of Portugal and Spain. Severe droughts in the Middle East and northern Africa have devastated the region’s water supplies, stirring conflicts. Depending on the response of the international community over the next decade, Earth’s average surface temperature is expected to rise anywhere from 2°C to 4°C by 2100

The tools used by climate scientists to make predictions of future weather and climate are called general circulation models (GCM). In a nutshell, GCMs are systems of differential equations that can be integrated over time to yield predictions about variables such as temperature, wind speed, and precipitation. These models are grounded in physics, their inner workings are easily interpretable, and simulating them yields reasonably accurate outputs. However, running the simulations is a computationally expensive process and it’s difficult to improve the models when given more data. This is where machine learning algorithms step in as a promising alternative. In particular, such algorithms have demonstrated competitiveness with traditional climate models in solving two sub-problems of climate modeling called “weather forecasting” and “spatial downscaling”.

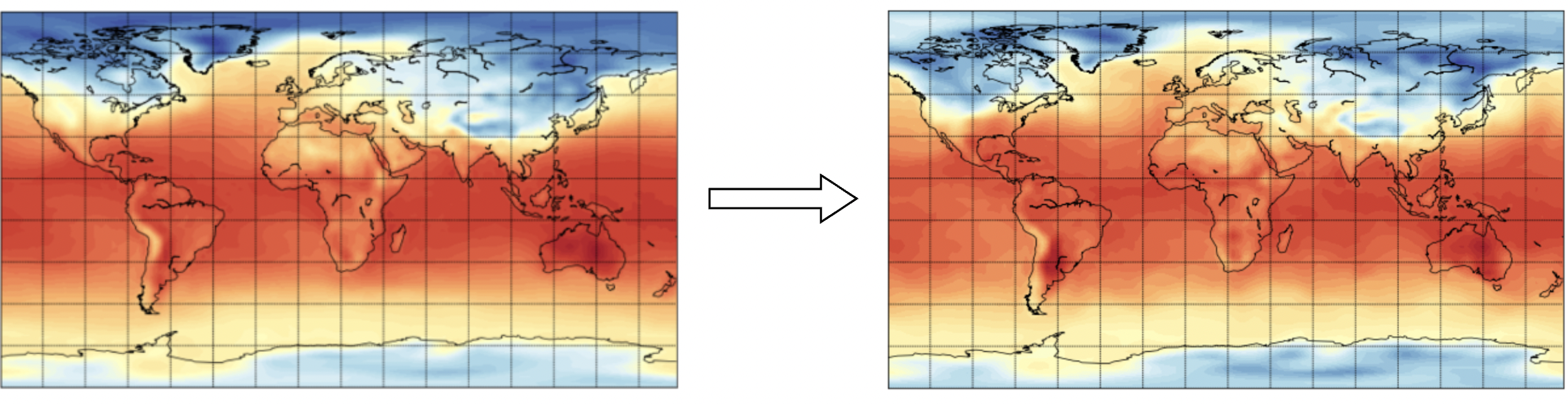

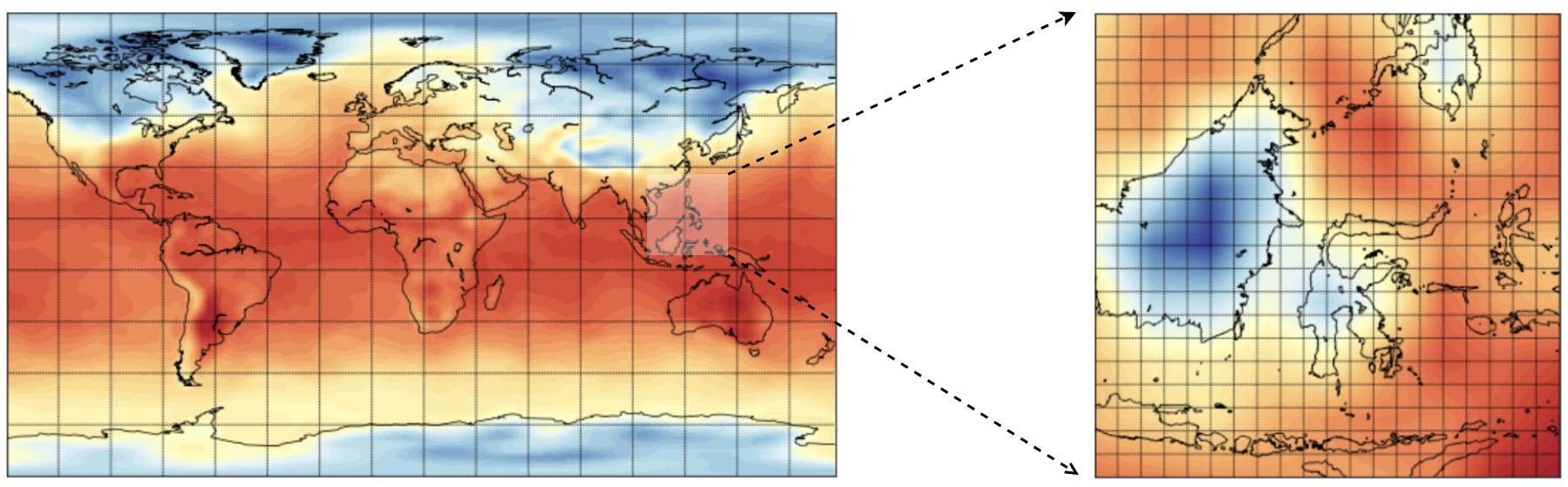

Weather forecasting is the problem of predicting climate variables into the future. For example, given daily surface temperature in Los Angeles, California over the past week, what will daily surface temperatures look like over the next week? Answering questions like this is analogous to the problem of video frame prediction in computer vision. Spatial downscaling is the problem of refining spatially-coarse climate model predictions (e.g., from a grid of 100 km \(\times\) 100 km cells to a grid of 1 km \(\times\) 1 km cells). This is similar to another computer vision problem called super resolution (SR), where the goal is to upsample low-resolution images. A key difference between forecasting/downscaling and frame-prediction/SR is that we can use additional signals to constrain the space of possible predictions. For instance, in video frame prediction, the machine learning model is given a sequence of images as input and produces a sequence of images as output. The input and output modalities are the same. In weather forecasting, the machine learning model can make use of exogenous variables in different modalities. Suppose that the model is predicting surface temperature. Future surface temperatures are not influenced only by past surface temperatures. Factors such as humidity and wind speed also play a role, and they can be provided as inputs to the model in addition to temperature.

Thus, as deep learning research has exploded in recent years, machine learning and climate scientists alike have begun exploring the application of deep learning methods to solving weather forecasting and spatial downscaling. However, the two communities approach the problem of applying machine learning in different ways. Climate scientists know what physical equations should be respected and what evaluation metrics are most important. Meanwhile, machine learning scientists know what architectures are best suited for what problems and how to process data in a way that is amenable to modern machine learning methods. Progress is impeded by confounding terminology (e.g., “bias” in climate modeling versus “bias” in machine learning), a lack of standardization in applying machine learning for climate science problems (e.g., defining appropriate train and held-out datasets, data augmentation strategies), and unfamiliarity with how to interpret climate data (e.g., reanalysis vs. simulated datasets, file formats such as NetCDF). This lack of a “lingua franca” is what motivated us to launch ClimateLearn.

We believe that good research needs to be supported by good infrastructure. In that spirit, ClimateLearn is a Python package for accessing state-of-the-art climate data and machine learning models in a standardized, straightforward way. In this package, we provide access to multiple datasets, a zoo of state-of-the-art baseline models, and a suite of metrics and visualizations for large-scale benchmarking of weather forecasting and spatial downscaling methods.

Datasets

ClimateLearn supports loading data from ERA5

Models

ClimateLearn implements a variety of baseline machine learning algorithms so that users can quickly get a sense of how machine learning can be applied to forecasting and downscaling problems. These include simple statistical methods such as linear regression, persistence, and climatology as well as state-of-the-art deep learning implementations for residual convolutional neural networks, U-nets, and vision transformers. Our baseline models have been well-tuned for the climate tasks, and are easy to extend for other downstream pipelines in climate science.

Metrics & Visualizations

The predictions of such models can be easily evaluated and visualized using ClimateLearn’s support for commonly used metrics such as (latitude-weighted) root mean squared error, anomaly correlation coefficient, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and mean bias. ClimateLearn also supports visualizations of ground truth, model predictions, and the difference between the two. Visual inspection of the predicted variables is a natural way of gaining an intuition about model performance and important outcomes.

Conclusion

Today we are launching ClimateLearn, a package that can bridge the gap between the climate science and machine learning communities through the provision of straightforward dataset access, baseline methods for easy comparison, and metrics and visualizations to understand model outputs.

Our roadmap for the future of ClimateLearn includes expanding support for more datasets such as CMIP6 (the sixth generation Climate Modeling Intercomparison Project)

Our aim in building ClimateLearn is to create a tool that can accelerate research at the intersection of machine learning and climate science, and we hope you are just as excited about it as we are.

This blog post was written to accompany our ClimateLearn is available on GitHub at this link: https://github.com/aditya-grover/climate-learn. We previewed some of its key features at a spotlight tutorial in the “Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning” Workshop at the Neural Information Processing Systems 2022 Conference.